Q&A: Bill Streever and Stuart Thornton

Moon author Stuart Thornton recently spoke with Bill Streever—bestselling author of In Oceans Deep, Heat, Cold, and more—about their mutual love of the ocean, history-making dives, and the urgency of conservation. Read on for a fascinating conversation—and to discover what all travelers can do to minimize their environmental impact.

Stuart Thornton: Bill, I enjoyed reading your book, In Oceans Deep, and it is a pleasure to be able to ask you a few questions. I know you split your time between Alaska and living on a sailboat, so I’d love to know where you are now?

Bill Streever: These days my wife and I are for the most part aboard our boat, Rocinante, a restored 1965 ketch, currently in Barra de Navidad, on the west coast of Mexico. Late last October, we left Cartagena, Colombia, on the Atlantic coast, and slowly made our way through the Panama Canal and then up the Pacific coast, visiting Guna villages on the lower Caribbean coast of Panama, spending a month or so in the Pearl Islands on the Pacific coast of Panama, and another month in Costa Rica. I think we first heard about the Covid-19 threat while preparing to cross the Panama Canal, and by the time we reached Nicaragua the scale of the threat was clear. When we arrived in Mexico, we stopped moving for a couple of months and lived a fairly isolated existence in an out-of-the-way marina in Chiapas, close to the border with Guatemala. Just before the wet season thunderstorms started in earnest, we sailed up the coast, taking advantage of isolated anchorages to break up the trip to Barra de Navidad.

Stuart: I live in Monterey, California, which is one of the best spots for diving on the California coast. I know you are a lifelong diver, and I was wondering if you’d ever been diving here before? And, if so, I’d love to hear about your experience.

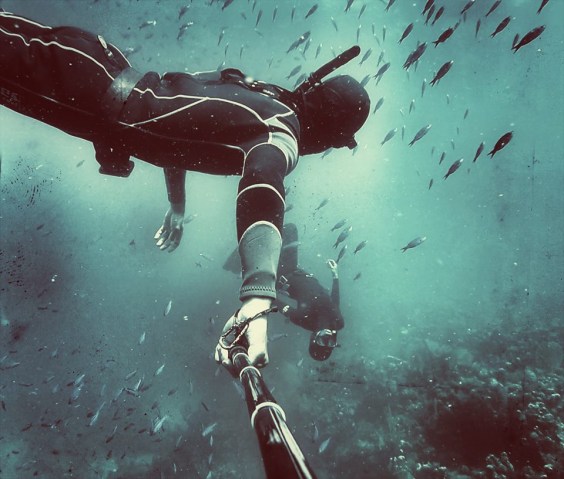

Bill: The diving in and around Monterey is absolutely fantastic. I first dove that coast in the late 1970s, when I was attending commercial diving school near Oakland, and I have been back several times since then. Of course, many tropical divers complain that diving in California is too cold, but for those who are comfortable in dry suits or in thick wetsuits the area around Monterey has as much to offer as any dive destination in the world. What are the highlights? I would put the kelp forests and their fauna at the top of the list, along with the chance to see marine mammals underwater. I also give high marks for any destination that allows divers to decide on their own level of comfort when it comes to independence, and the area around Monterey definitely offers that flexibility; there are dive boats and dive guides for those who want them, but there are also endless opportunities to dive independently from beaches, from dive kayaks, and from small boats. And the weather, of course, is tough to beat.

By the way, the diving opportunities are also spectacular further up the west coast, especially around Vancouver Island and in parts of Southeast Alaska.

Stuart: Being a lifelong ocean enthusiast myself, there’s something invigorating and nourishing about being in the sea. How would you explain it?

Bill: I’m not sure there is a logical explanation behind a love of the ocean. When you think about the ocean rationally, it offer lots of inconveniences—salt water, weather conditions that often range somewhere between uncomfortable and dangerous, for most people the likelihood of seasickness, lots of opportunities to be stung by various kinds of marine life, the corrosive effects of salt on anything with metal parts…. But thankfully we are not entirely rational beings, so many of us—most of us, I think—find something to love about the ocean. And of course that “something” is different for each of us. For me, I am drawn by the ocean’s biodiversity, by its often wonderful and wondrous richness of life. But I am also drawn by the ocean as an ever-changing wilderness. And I am drawn by a sense of history—humanity has a very long and colorful maritime history, and I think far too many people today have lost sight of that reality. And I am drawn by the constant challenges posed by the sea.

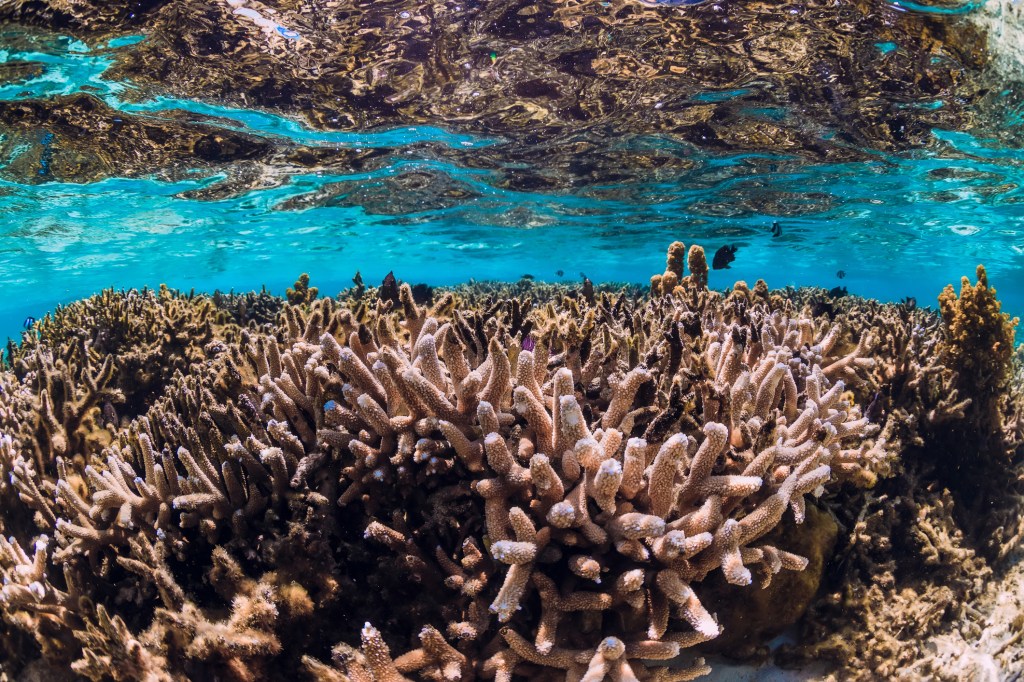

Stuart: With In Oceans Deep, you set out to write about humanity’s presence underwater, but in the end, you were compelled to write about ocean conservation as well. Why did the topic of ocean conservation feel unavoidable to you?

Bill: Almost everyone I interviewed for the book—here I am talking about ocean scientists and engineers for the most part—brought up conservation issues during interviews. Most importantly, when I interviewed Dr. Sylvia Earle, I wanted to focus on her work as a famous underwater explorer, and in particular I hoped that she would talk about what it is like to be in a position to inspire young women who are interested in underwater exploration. But she kept turning the conversation back to ocean conservation. She really was not interested in discussing her achievements as an underwater explorer or even her achievements as a scientist. Her message was conservation, conservation, conservation. So after that interview I reviewed my notes from earlier interviews, including those with pure engineers, people who by their own admission knew almost nothing about biology, and almost every one of them had talked at least in part about the importance of conservation and about how the oceans had changed in their lifetimes.

But in addition to the interviews, there is of course the matter of personal experience. Anyone who has spent a lifetime on and around oceans cannot help but notice the changes that have occurred. There are subtle changes that we might not know about without collecting sophisticated measurements over many years, but there are other changes that are absolutely shocking and in-your-face.

And while I was working on this book I was afloat, moving from places with fairly high environmental standards, like the Bahamas, to places like Haiti, where people still openly talk of eating sea turtles and even dolphins.

Conservation was an inevitable part of the story of humanity’s presence beneath the waves. I did not want to write a book about conservation, in part because conservation books tend not to find many readers, but conservation is absolutely part of the story, and in fact an important part of the story.

Stuart: Also in the book, you detail the amazing story of Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard’s 1960 history making dive in a submersible to 35,814 feet deep into the Mariana Trench, the deepest oceanic trench on Earth. Why do you think this story is so little known?

Bill: As part of my response to this question, I have to say that the brief time I spent with Don—I interviewed him at his home office—made the writing of this book worthwhile to me, personally. Don is the most inspiring person I have met in my life.

Why don’t people remember the Trieste dives and especially the 1960 dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep? Well, some people remember, but the Trieste expedition was overshadowed by the space missions of the time. And although going to the deepest point in the world’s oceans presents incredible challenges that are in many ways comparable to those of going into space, the original Challenger Deep dive was done quietly, with a very small team. The U.S. Navy was behind the expedition, but even within the Navy career-minded senior officers were cautious about involvement with a program that had at best limited military applications and that could at worst lead to tragedy. Don was the commanding officer of the expedition, and at the time he was only a lieutenant, and the average age of the men under his command was in the mid-twenties.

After the Challenger Deep dive there was some publicity, and Piccard published a book about the program that I remember reading when I was a kid. But then the program was more or less forgotten. Space offered cool equipment, roaring rockets, and unbelievable vistas, while the Trieste expedition offered two guys cramped in a tiny sphere hung from the bottom of a gasoline-filled buoyancy chamber seven miles down in a very dark and very cold ocean.

As an aside, today the same number of people who have walked on the moon have visited the Challenger Deep—that is, twelve people.

And you know, space continues to attract more attention than the deep sea. The recent remarkable achievements of the Five Deeps expedition have attracted some attention, but nothing like the attention garnered by the SpaceX launch. Why is that? I don’t know. I don’t get it.

Stuart: My guidebooks cover the coast of California. I was wondering if you have any advice for my readers and I on how to sustainably experience the coastline and the Pacific Ocean while traveling?

Bill: I think most of us at this point know the basics—avoid unsustainably harvested seafood (or just avoid seafood altogether), avoid plastics, minimize carbon footprints. Even in choosing how one travels, it is worth considering the footprint that your travels might generate. Flying first class, for example, generates far more carbon per person then flying in the back of the bus, and local travel generates far less carbon than travel requiring flights. I am not saying that people should stop traveling, but rather that they should think about how they are traveling and how it affects the world. At the very least, think about and acknowledge to yourself the impacts that result from your leisure activities, and ask yourself if you are comfortable being responsible for those impacts. If not, change the way you travel.

Just as importantly, or maybe more importantly, I think people should talk about their travels to friends. What did they see? What did they learn that can change the way they interact with the world? People are overwhelmed with information from all kinds of sources, and most of that information just becomes a sort of background noise, but people still listen to their friends.

Stuart: What is the biggest threat to the health of our oceans, and what can we do about it?

Bill: In my opinion, there is no single biggest threat. The oceans are dying the death of a thousand cuts. There is overfishing, ocean acidification, warming, nutrient pollution, toxins, noise pollution, oil spills large and small, exotic species introductions, unbridled coastal development, and a host of other insults, all working together to have a negative impact with a sum that far exceeds its parts.

What can we do about it? Reduce our own personal contributions to every one of those cuts in any way that we can, and pressure those around us to do the same—by those around us, I mean our friends, but also corporations and government entities.

Stuart: You’ve written about some of the world’s most extreme places in your books In Oceans Deep, Heat, and Cold. Do you plan on writing about another extreme environment for your next book or might you enjoy penning a book about a more comfortable locale?

Bill: Well, I know that I have been represented as someone who writes about extreme environments, but I have never seen myself that way. I write about places and situations that I love. Now I am working on a book about the sea. Is that an extreme place? I suppose some will say that it is, but to me it is not so much extreme as it is extraordinary.

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use