Q&A: Caroline Van Hemert and Lisa Maloney

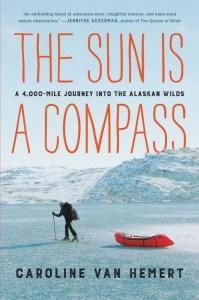

Moon Alaska author Lisa Maloney sat down with Caroline Van Hemert—author of the award-winning memoir The Sun is a Compass—to talk all things Alaska, adventure, and the powerful lessons learned from a once-in-a-lifetime journey.

Lisa Maloney: In The Sun Is a Compass, you write about how trekking four thousand miles under your own power solidified your connection to the land and (re?)awakened a sense of wonder. Now you live in Alaska’s largest city. Is there a trick to maintaining that sense of connection and wonder in a relatively urbanized setting?

Caroline Van Hemert: Pat and I do our best to strike a balance between an adventurous existence and one that fits with our family and professional needs. When we’re not traveling, we divide our time between Anchorage and a remote, off-grid cabin in southeast Alaska. In Anchorage, we live near my parents and my sister’s family and our boys attend preschool and kindergarten.

Pat owns a design-and-build company and I work as a research biologist. Even in Alaska’s largest city, there are plenty of ways to connect to the outdoors; solitude is usually within a couple hours’ hike. When in town, we take advantage of the extensive trail networks and excellent backcountry skiing access.

At our cabin, which Pat and I built by hand from trees on the property, every day has an element of adventure. Our only regular visitors are of the furred or feathered variety and we live by the rhythms of the weather, tides, and seasons. Our relationship with the land is very immediate here, but I don’t think a true “wilderness” setting is necessary to feel inspired and connected.

What grounds me in both places is the desire to be outdoors, move my body, and search for signs of wonder, whether in the form of a pod of orcas passing in front of our cabin or a chickadee prospecting for a nest site in downtown Anchorage.

LM: Toward the end of the book, as you and Pat are nearing your final destination of Kotzebue, you mention that “tonight, [a] bent, sooty stove ranks among my favorite objects on earth,” because it made cooking meals so much easier than working over an open fire. Does anything jump out at you as being similarly meaningful in your everyday life now?

CVH: Part of the appeal of venturing out with only what we can carry on our backs or in our boats is the ability to simplify our needs to their most basic forms—food, shelter, safety, and love. In this way, I’ve found that backcountry travel also offers the perspective of gratitude for the small stuff. It was not the stove I loved so much as the fact that one of the hardships of our daily lives—cooking with open fire—was suddenly replaced with the gift of a much easier option. In this way, living simply at our cabin and taking trips that require us to make physical sacrifices help remind me of how little I actually need.

LM: You’ve had a much more intimate, and extensive, experience of the Alaska wilderness than most people will ever get. Which moments or encounters have stuck with you the most?

CVH: Although many wildlife encounters have moved me, one of the most influential experiences of my life occurred when we crossed paths with the Western Arctic Caribou Herd on the Noatak River. After being thwarted by early season snow in the Brooks Range and waiting in the tent without food for five days, we witnessed thousands of caribou swimming across the river. It was a gift I couldn’t have imagined before that day.

I described this experience in a recent article for The New York Times: “On that rainy afternoon, in the collective energy of bodies in motion, hurtling themselves into the current of a cold Arctic river, grace abounded. For hundreds of miles we’d traveled in the shadow of caribou, trusting their wisdom to guide us over terrain that often felt impenetrable. By following their hoof prints and rutted tracks across the mountains, we’d learned that there was always a way forward. When a caribou calf stopped to sniff me then skittered away to join the others, I realized I’d found what I was looking for. Faith in the unknown. Beauty when I least expected it. The visceral relief of bearing witness to something much larger than myself. After nearly starving on a riverbank, the delay in our food resupply felt serendipitous beyond belief.”

LM: Much as you and Pat stepped into an adventure unlike anything you’d faced before, the entire world is entering a new experience together: It’s been generations since the world has faced anything like the current COVID-19 pandemic. None of us know how or when it’ll be resolved, and how this period of upheaval will affect our lives.

Can you talk about how your experience of trekking across Alaska informs your response to the changes happening in our world now? Do you have any advice for people who are struggling to stay grounded, focused, motivated or calm through this experience?

CVH: My greatest take-away from our journey was to accept the uncertainty inherent to being human. Of course a certain level of ambiguity exists in everyday life, but its lessons in the backcountry are impossible to ignore. For six months, I woke up each morning not knowing what the day would bring. Around the next bend we might find an aggressive bear or a herd of migrating caribou, a rocky impasse or a tundra-covered valley rich with blueberries. There was little point in worrying about what we couldn’t control.

In the process, I became extremely focused on the present. This is arguably easier to do when faced with the immediacy of a bear trying to eat us than the looming specter of a virus that will affect our lives for many months, if not years. However, the shared element is in the tedium. Something always hurt, my feet were constantly wet, and at times the mosquitoes were so intense that we couldn’t breathe without headnets. And yet, one paddle stroke, one step, one swish of the skis at a time, we made our way across 4,000 difficult miles.

I eventually began to trust that no matter what challenges presented themselves, we would find what we needed along the way. I don’t think of this in terms of blind faith so much as an overriding sense of endurance. I take many of my lessons from birds and other wildlife—from bar-tailed godwits that travel 7,000 miles nonstop to chickadees that survive at forty degrees below zero, they show us the limits of what’s possible in the face of adversity.

In terms of practical advice, I’d suggest taking a few minutes each day to indulge in a small pleasure—reading a poem, eating a piece of chocolate, being present with your children—without asking anything more of yourself. If you have access to the outdoors, make yourself go out at least once a day, even if it’s raining or cold. This can mean a slow walk in the woods or a jog around the same four city blocks. I’ve found that doing this first thing in the morning helps my outlook, even if it comes at the expense of an extra hour of sleep.

When you’re outside, look to the sky—birds don’t care about the pandemic. Springtime is unfolding everywhere and something in the natural world will almost certainly amaze you, no matter where you call home.

LM: Very early in the story, you described feeling like you’d already failed. Throughout the rest of the book, you remained very honest about your doubts and fears as you faced dangerous situations and unknowns. How does being on the other side of that experience affect your decision-making process and sense of adventure today?

CVH: Pulling off such an ambitious journey both humbled us and emboldened our sense of possibility. Occasional failure is a necessary part of dreaming big. However, it’s also important to make the distinction between accepting failure and confronting adversity. Just because something didn’t work as planned doesn’t mean it’s time to give up. In fact, if we had, we’d still be sitting on a beach somewhere in British Columbia waiting for the perfect weather window.

On the trip, we developed a deep sense of trust in each other and in the iterative process we use to make decisions. Now we have two young children and we’ve adapted adventure to fit into our lives as a family. Most recently, we sailed up the Inside Passage with a one- and a four-year-old.

In many ways, being an outdoor adventurer is excellent preparation for being a parent. Identifying potential hazards in the backcountry is quite similar to predicting all of the ways a toddler can wreak havoc for themselves and others in a confined space.

Both of these experiences also expose the raw truth of being human—there are many things we can’t control in our lives and our surroundings. However, we can choose to take on challenges that force us to grow and learn, and be willing to accept that this will come with hardships along the way. While we continue to be very calculated in our risk-taking, we also approach adventure with the knowledge that we’re capable of more than we had ever thought possible.

LM: In The Sun Is a Compass, you mention that one of the most basic of human desires is to see what’s around the next bend. What’s around the next bend for you?

CVH: There’s so much uncertainty in the world right now, especially in the context of travel, but we continue to dream about our next adventures. Pat and I continue to do adult trips on skis, packrafts, and foot, but much of our energy has been directed toward exploring new horizons with kids.

We’re excited to continue sailing as a family and we’d like to venture into Arctic waters by boat, perhaps linking this with land-based adventures. As our sons get older, they are becoming more capable and thus far have been very willing adventurers. Pat is scheming about building an Umiak (traditional Inuit skin-on-frame open rowboat) on our beach with the boys this summer. If we build it, we’ll certainly have to take it somewhere!

On the professional front, writing has been a new journey for me and I’m excited to follow this passion while still pursuing my wildlife research. I’m increasingly drawn to the connections between science and storytelling and hope to start work on another book project soon.

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use