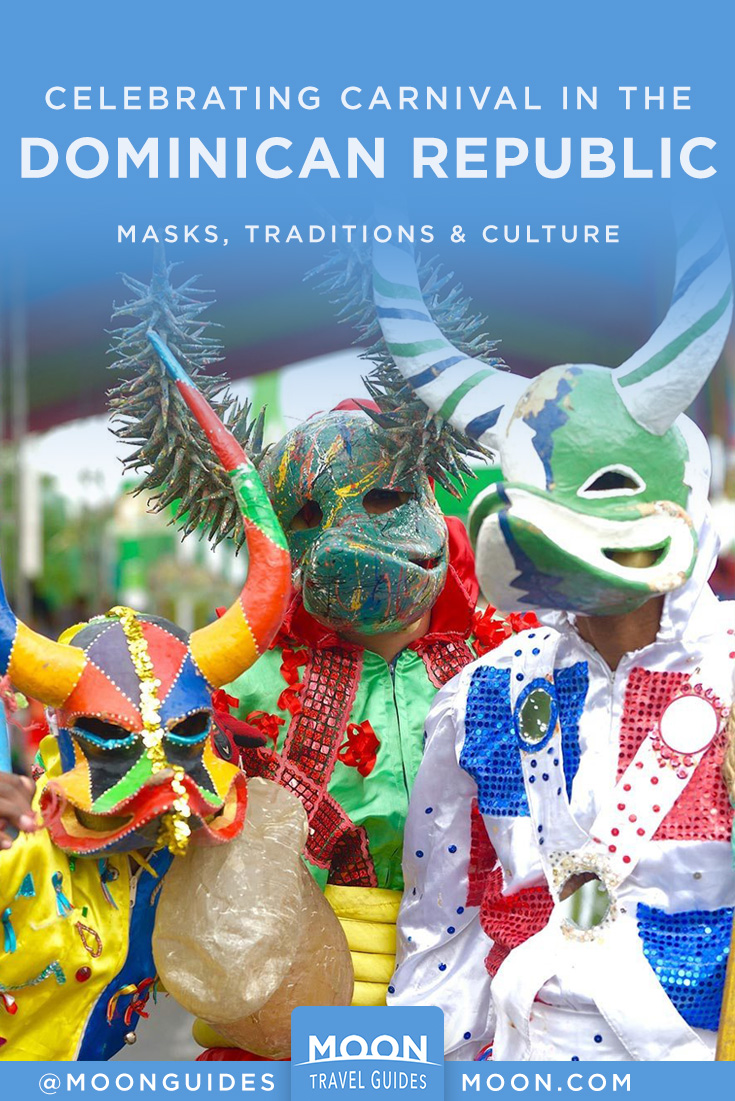

Carnival Dominicano: Masks, Traditions, and Culture

The single biggest celebration of culture in the Dominican Republic takes place during the month of February. Carnival celebrations unite Dominicans from all walks of life and of all ages as everyone takes to the streets as participant or spectator. Parades kick off in the country’s main regions and cities pre-Lent on the first Sunday of February. They continue every Sunday of the month, culminating with Independence Day festivities on February 27.

A tradition that dates back to the Spaniards, who brought it to the island in the 15th century, Carnaval Dominicano is the oldest carnival in the Caribbean region. It metamorphosed after contact with indigenous and African influences, as residents used it to make fun of the colonial masters in their elaborate costumes. Over the years, it turned into a Dominican version comprised of characters that tell the history, and folklore of the country’s various provinces, and reflect Dominicans’ mixed heritage. Diversity is indeed the cornerstone of Carnival in the DR. From the more Taíno influenced north coast costumes to the African influenced southwest, it’s a vibrantly cheerful part of the Dominican Republic’s history, culture, and people.

The cities with the oldest Carnival traditions in the country are Santo Domingo, La Vega, Santiago, Montecristi, and Cabral. Although former dictator Rafael Trujillo prioritized the “social carnivals” for the elite and created separation of the classes with private club performances, the Dominican people rose above and turned it into a celebration for all.

Each city or province has its main Carnival character: a limping devil or diablo cojuelo with respective masks. Why is it limping? The legend says that this devil was so mischievous that it was banished and pushed down to Earth, and left with an injured leg turned lame.

If you don’t see some form of devil at Carnival, you’re not in the Dominican Republic. In addition, parades include Dominican folklore personalities and comparsas groups in varying costumes, with specific messages that range from the comical to the political. No two parades will be the same, allowing you to hop around the entire month across the DR’s thirty-one provinces to see the range in roots and traditions.

Carnival ends the first Sunday in March with the grand Desfile Nacional, or National Parade in Santo Domingo—on the heels of Independence Day celebrations. The most popular Carnival devils and groups from the thirty-one provinces descend on the Malecón (the city’s seafront boulevard) and compete for national prizes. This final parade is the longest, most spectacular display of diversity and creative costumes you’ll see anywhere in the Caribbean. In 2016, over 170 groups paraded, from 2pm to about 9pm.

Below are thirteen of the main carnival characters from around the Dominican Republic, and the meaning behind the elaborate masks, costumes, and personalities of Carnaval Dominicano.

Dominican Republic Carnival Masks and Characters

La Vega’s Diablo Cojuelo

Dating back to the 1500s, Carnaval de La Vega or Carnaval Vegano is the biggest, most vibrant carnival celebration in the Dominican Republic. Its principal character, the diablo cojuelo or limping devil, is instantly recognized because of the exaggerated mask features, with protruding eyes and teeth.

Dressed in a cloak, shiny shirt and broad trousers covered with bells, mirrors, and ribbons–all meant as a mockery of the Spanish medieval knights–the devils scare the crowd away with their giant masks and their whips. Each group of these limping devils from La Vega design and handcraft their masks every year, months ahead of Carnival, and hidden from the competitors.

Carnaval de La Vega is also one of the most commercially sponsored carnivals in the country. Masks have evolved over recent years to become more oriental and baroque in their features, which many criticize. But they still impress with their larger-than-life costumes as crowds spill all over the streets for one big, small-town party.

The Vejiga: The Devil’s Weapon

A defining characteristic across the country’s Carnivals is the devils’ use of vejigas, inflicting pain on anyone in their path. These aren’t your regular whips: they are made of a cow’s dried, inflated bladder, cured with lemon, ashes, and salt. They are so hard to the touch that anyone who receives a vejigazo on their buttocks may be bruised for weeks. Watch your behind! The sisal rope seen in this image is used by Santiago’s devils as an additional weapon; the Cachúas from Cabral also use their own version of a fouet.

La Vega’s Carnaval de La Boa

Held in the morning, prior to the main La Vega Carnival a couple of streets away, is the less publicized Carnaval de La Boa. This is a traditional version of how Carnival used to be celebrated in La Vega 50 years ago–with simpler costumed devils with whips, who dance, leap, and pose with children. It stretches just one block, but is a popular pick for families.

Los Lechones of Santiago

Carnaval de Santiago is the second most popular Carnival in the country after La Vega. It’s one of the most creative and colorful, and among the liveliest in crowd participation around the city’s iconic Restoration Heroes Monument. Santiago’s reigning carnival characters are the lechones or “piglets”—devils in masks that resemble the face of a pig (Santiago’s pork is renowned). They aren’t scary because of their tall horns, but rather have a curved, long snout. There are hundreds of participating lechones groups–with variances in their masks and costumes to denote their neighborhood.

The two most popular are Los Pepines, with tall, pointed snouts but smooth horns, and Los Joyeros, with masks that are spiked with numerous thorns. Their clothing is similar, and consists of a long-sleeved shirt and pants made of silk, adorned with sequins, beads, and mirrors, and fitted with a wide belt.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Santiago’s devils open up the parade as they were originally considered the guardians of carnival or vejigantes, warding off the crowds and keeping order in the streets.

Fear of the lechones is due to their signature fouet or sisal rope, which they swing mercilessly up in the air at high velocity above their heads, before it hits the ground with a loud bang. You will shudder at the sound of the air whistling above you. You don’t want to be within its range–remain behind the sidewalk barricades for safety. They also carry a vejiga in the other hand to swing at participants’ rear ends if they are in their way. Between cracking whips and hitting bottoms, the lechones dance a style of African dance, swinging their legs side to side and lunging forward.

Los Taimáscaros of Puerto Plata

Puerto Plata’s most popular devil characters are Los Taimáscaros, made of the words Taíno and “mask.” A group of young men from Puerto Plata created this identity in 199 to help uplift the community spirit while reinforcing the trio of cultures that represent them as Dominicans: Taíno, African, and European. To date, there are about thirteen active tribes forming the Taimáscaros group. Within that group, the most popular are Tribu Yucahu, who have won multiple awards over the years for their ingenuity in costume and dance, including the highest national Carnival prize. The Taimáscaros’ masks reflect the face of a Taíno god or deity, while the costumes incorporate their other heritage.

Los Guloyas of San Pedro de Macorís

A unique Afro-Caribbean group in the Dominican Republic are the Cocolos: the descendants of enslaved Africans who were brought to the DR in the late 19th century from the British islands of the Caribbean. Approximately 6,000 originally came from Anguilla, Barbados, St. Kitts, Nevis, Tortola, Turks and Caicos, and St. Croix, among other places, to work in the DR’s sugar industry. Dominicans first gave them the name Tortolo—assumed to have derived from Tortola in the BVIs—which later evolved into Cocolos. Their dancers, known as the Guloyas, participate in the Carnival and wear gorgeous, beaded costumes with feathery hats. They dance to their own drums and twirl happily in the streets in their unique Afro-Caribbean moves. UNESCO classified the Guloyas in 2005 as a masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Los Pintaos of Barahona

Some of the comparsas or carnival groups have more recent origins yet carry great cultural significance. The southwest town of Barahona is known for Los Pintaos–the painted–a group created in 1997 by Francisco Suero Medina, locally known as El Gato. They made their debut in the national parade in 2000, and in 2008 were awarded the highest Carnival award granted by the Ministry of Culture: the Premio Nacional de Carnaval Felipe Abreu. The Pintaos represent the Maroons, who rebelled against Spanish colonialism and slavery and took refuge in the mountains of Bahoruco, southwest of the DR, in the early 16th century. Their costume is the intricate paint that covers their naked body, save for a piece of cloth covering their private parts. They dance in the street, sometimes holding sticks, and spread their joy and rebellious nature to the crowds, celebrating the Maroon heritage. They’re unmistakable at Carnival and are a cultural icon of Barahona.

Las Cachúas of Cabral

The southwest also has a devilish character inspired from the days of Maroon resistance in the mountains of Barahona: Las Cachúas, from the town of Cabral. The Cachúas make an appearance at the National Parade, but are mostly known to participate in the Carnaval Cimarrón or Maroon Carnival, spanning three days at the end of Holy Week. It’s the last of all the carnivals to be celebrated in the country, as it’s held during Easter. They wear a mask made out of vibrant papier mâché, as they roam all weekend with whips starting at midnight on Holy Saturday. It all ends with a big, loud folkloric ceremony on Monday after Holy Week, when they burn Judas in effigy in the village cemetery.

Los Indios

In areas such as Santo Domingo, Puerto Plata, and La Vega, you will see various groups representing the Taíno, first inhabitants of the Dominican Republic who were exterminated by the Spaniards through disease and murder. Adults and children dress up in grass skirts and feathers, bodies smeared in brown paint, torsos bare for the men. They carry bows and spears.

Los Brujos of San Juan de La Managua

It was believed that there once were witches living in the southwestern city of San Juan de La Managua. Witchcraft was a common practice, hence the name of one of the Carnival troupes from this region.

Los Chiveros de Dajabón

To showcase the importance of farming in the area and its gastronomy, participants from this border town with Haiti wear masks resembling goats.

El Roba La Gallina: The Hen Robber

It’s not all about scary devils and whips in Carnival. Some are fun folkloric characters that are meant to evoke laughter. The most beloved is El Roba la Gallina or the hen robber. This is usually a man dressed up as a woman in an extravagant layered dress, with huge breasts, hips, and elaborate makeup, who goes around the neighborhood colmados or shops begging for food, money, or sweets for her pollitos or children. She carries a big purse, handing out candy to the crowds, while she would later steal chickens and shove them in that emptied bag. Crowds burst into laughter as Roba La Gallina performs at Carnival, dancing and shaking her bottom as she parades down the streets and sings the rhyme, “ti-ti manatí, ton ton, molondrón, roba la gallina, palo con ella!”

The Comparsas

These numerous carnival dance troupes bring a lot of life and fun to Carnival. Each has its theme–often a dramatic, comical representation of political, social, or religious issues. While there’s no record of how far back the carnival troupes have existed, they are thought to have come from Cuban influences, during their migration to the DR in the late 19th century. The above is a member of the Comparsas Zoomorfas.

Other groups to look out for at Carnival Dominicano are the Platanuses from Cotui, whose devils cover themselves in plantain leaves, the Toros from Montecristi, with masks representing bulls, and the Travestis (the Transvestites), who are crowd favorites.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Pin it for Later